Another Look At NFL Positional Value

Hi folks, I’m back again with another post about positional value heading into the NFL draft. This time, I take a look at when teams are drafting particular positions—first round, second round, or later? I also look at how draft picks perform based on their position. Are teams likely to find quality quarterbacks outside of the first round? What about edge rushers or cornerbacks? Answering that question can help teams figure out where they should focus their early draft assets, especially when combined with an understanding of which positions can get filled in free agency and at what cost (which I covered in a previous post).

Like any good overzealous NFL fan, I’m spending a lot of time these days thinking about the upcoming NFL draft in April—undoubtedly too much time. One of the things I’ve been toying with lately is finding ways to assess which positions to target in the draft, ignoring the prospects of individual players—what I’ve been calling “positional value.” I previously looked at positional value from a money standpoint by looking at which positions teams focus their salary cap spending on. From that vantage point, it’s apparent that quarterbacks take home the lion’s share of team spending, with edge rushers a distant second. Wide receivers, defensive tackles, offensive tackles, and cornerbacks are the next tier, while other positions like center, running back, tight end, and off-ball linebacker are clearly not valued as much and net much smaller contracts.

But there are of course other ways to look at positional value, so I wanted to talk through some of them.

Which Positions Do Teams Actually Prioritize For Their Best Draft Picks?

One thing I wanted to look at is when teams actually draft particular positions. The NFL draft has seven rounds, so we can try to assess positional value by looking at which positions typically get drafted higher in the draft. It’s a relatively simple task in concept, but there are some things I had to clean up to get good positional groupings since teams may draft a player who played one position in college intending for them to play another role at the pro level. For example, a fair number of college cornerbacks get drafted with the expectation that they’ll ultimately play safety in the NFL; same thing for college tackles who may profile physically as NFL guards.

Using info from Pro Football Reference, I pulled every draft pick from the last 10 drafts and categorized each player (excluding pure special teamers like kickers, punters, and long-snappers) into the following positions: quarterback, wide receiver, tight end, running back, offensive tackle, offensive guard, center, edge rusher (includes defensive ends and 3-4/rush linebackers), defensive tackle (aka interior defensive line, same thing), linebacker (off-ball), cornerback, and safety.

There are a few house-keeping items I wanted to acknowledge off the jump, specifically regarding how I selected player’s on-field positions as of the time they were drafted.

I checked what position each player in fact played during their first few years in the NFL to confirm they were slotted correctly. For example, I categorized Micah Parsons as an edge rusher even though he played off-ball linebacker in college, as Dallas moved him to edge rusher in the summer leading up to his rookie year. This is obviously an imperfect way of handling things, and there is some degree of my judgment baked in. I did my best, and I’m happy to email anybody the list of positions I used for each player if you’re curious.

I chose not to divvy up positions further than the categories described above. That was deliberate. I didn’t draw distinctions between left and right offensive tackles and offensive guards, as those positions shift a lot from where guys play in college, or even from where NFL teams initially hope they will land—quite often, players drafted in the hopes they will eventually be left tackles or left guards often move to the right side if their skill sets are better suited there or if a greater need develops on that side of the line for a particular team.

I also didn’t draw any distinctions between slot, X, and Z wide receivers, nor any distinctions between boundary cornerbacks and nickel/dime cornerbacks. Players often switch between those roles in different coaching schemes after they’re drafted, and it’s really tough to get reliable data at scale. I note this just because conventional wisdom suggests that left tackles/guards are more valuable than right tackles/guards, X/Z receivers are more valuable than slots, and boundary corners are more valuable that nickel/dime corners. I don’t dispute any of that, but it’s more than I set out to address here.

Finally, I chose 10 years of draft data on purpose, though I admit it’s a bit arbitrary. Things change quite a bit in the NFL over time, and I didn’t want to go so far back that it would mask current trends. For example, 20 years ago, running backs were highly sought after, but it is pretty evident that is no longer the case. Going too far back into the past runs a very real risk of including too much historically dated information to make any analysis about the current NFL useful. On the flip side, I also didn’t want such a small time period that it would be impossible to draw any meaningful conclusions from having too small of a dataset. Thus, 10 years seemed about right.

So, where are teams spending their picks?

[Figure 1]

Figure 1 shows the percentage of players drafted in each round for the 12 positions I looked at over the course of the last 10 drafts, from 2014 through 2023, as well as the total number of players drafted at each position (at the bottom in parentheses).

There’s a fair amount that can be seen from this chart, but I want to focus on what I found most notable in particular.

A very high percentage of drafted quarterbacks (almost 28%) are drafted in the first round, but there’s a relative dearth of quarterbacks taken in the second round (under 7%). At the same time, there isn’t really anything notable about the proposition of QBs getting drafted in rounds 3-7. That suggests QBs who aren’t quite first round talents are often getting pushed up from the second round. That does appear to happen—for example, the Ravens and Vikings traded up from the second round to the very last pick in the first round to draft Lamar Jackson in 2018 and Teddy Bridgewater in 2014, respectively. Surely this trend is in part because teams can also secure a fifth-year of team control for first round picks, which can lead to significant financial value for the team if the player winds up being successful, especially for QBs.

After quarterbacks, teams appear to select a high percentage of their offensive tackles and edge rushers in the first round. Over 19% of drafted offensive tackles and nearly 18% of drafted edge rushers are taken in the first round. That makes sense given the premium teams place on these positions in free agency. Also, for offensive tackles in particular, there may be a similar trend of players getting pushed up from the second round to the first round as with QBs, although it’s less pronounced—there’s a big drop-off from the percentage of players taken in round 1 to round 2 compared to other positions.

Just like with free agency spending, teams do not want to spend up, in terms of early draft capital, on low-value positions in free agency like tight end and running back. Only about 18% of drafted running backs and 20% of drafted tight ends are taken in the first two rounds. A similar trend occurs withs with drafted guards (about 20% taken in the first two rounds) and linebackers (about 17%). I was a little surprised to see how low the percentage of guards taken in the first two rounds was. Even though it’s not a “high value” position, it’s still higher value than RB, TE, and LB.

Teams appear to use a high proportion of middle round picks on the lower value positions I just described. Around 54% of tight ends, 50% of running backs, 55% of guards, and 50% of linebackers are taken in rounds 3 to 5 —tight ends, running backs, guards, and linebackers. Compare those numbers to quarterbacks and offensive tackles, centers, and cornerbacks, where around 39% to 41% are taken in the middle rounds.

There’s a weird thing going on with centers, who teams appear to typically forgo in the first round and prefer in the second round. Only 9% of drafted centers are taken in the first round, but over 30% of centers are taken in the first two rounds taken together. I am not sure there’s an obvious reason behind this trend, but it definitely stands out amongst the lower value positions. This could be coincidence given the relatively low number of centers drafted compared to other positions.

I was surprised to see that wide receivers and cornerbacks are pretty evenly drafted through the seven rounds. They’re among the highest value positions in the free agency market, so I would’ve guessed that teams were drafting them more frequently in early rounds. I will flag that the fact that my dataset doesn’t distinguish between slot and boundary players is probably masking some trends. In addition, it’s also worth noting that WR and CB are usually the two deepest positions on NFL rosters—most teams carry 5+ receivers and corners respectively—so it makes sense that teams have to draft a lot of them.

It’s notable that defensive tackles haven’t been drafted all that early relative to edge rushers. Only about 22.5% of defensive tackles are taken in the first two rounds compared to about 33% of edge rushers. For years, conventional wisdom has said that edge rushers are more valuable given their pass rushing role, but that weighting has changed a lot in recent years. More and more DTs are becoming elite pass rushers (Aaron Donald comes to mind), so they’re getting paid like it. The free agency spending data I looked at previously showed that DTs are the fourth highest paid position based on average annual contract value, trailing only QBs, edge rushers, and WRs. And at the top end, DTs are paid pretty closely to edge rushers—the top 20 DTs are paid about 90% of what the top 20 edge rushers get in terms of average annual contract value—so I would’ve expected edge rushers to get a slight advantage in the early draft rounds, but it’s still more than I would’ve thought.

By looking at where teams draft particular positions over time, we can get some insight into how NFL teams on the whole are valuing different positions without getting bogged down too much in individual talent evaluations. Combined with looking at positional spending, we can get a pretty decent picture of which positions are priciest in terms of dollars and assets (draft picks) in order to weigh where to allocate resources. Unsurprisingly, the two markets show a fair amount of similarities. The two markets agree that QBs are the most important position and price them accordingly (big dollars in salary, and first round pick expense in the draft). Both markets also seemingly agree that edge rushers and offensive tackles are premium positions, while RB, TE, LB, and safety aren’t. Some of the other positions present some interesting value opportunities. For example, WR and CB are expensive positions to fill in free agency, but team’s aren’t necessarily allocating their early draft picks to those positions disproportionately—that suggests there’s value to be had by drafting those positions rather than filling them with veteran talents at market prices. Centers might be the opposite—it’s a really cheap position to fill in free agency, but a big chunk of centers are getting drafted in the first two rounds.

Can You Prioritize What Positions to Draft By Looking At Production?

One of the benefits of determining the relative value between the various positions is figuring out which positions to focus on during the draft. If a given position is expensive to fill in free agency, such as quarterback or edge rusher, it makes sense that teams would benefit from filling that position through the draft where salaries are set to a rookie scale for up to five years for first round picks (four years for non-first round picks). Of course, the biggest potential values also come at the high-end of each position.

A top 10 overall NFL edge rusher can command around $25 million or more per year in average compensation, which will lead to a comparable salary cap hit (before cap manipulations to push cap hits into different years). A top 10 center is likely to command somewhere between $10-13 million in average annual compensation. Meanwhile, the #1 overall pick in this year’s draft (the highest compensated draft slot) draft will have a 2024 cap hit of just over $7 million per Spotrac. In other words, a team will save about $18 million or more in cap space by drafting a defensive end that performs comparably to top 10 edge rusher, but they would only save about $3-6 million in cap space by drafting a top 10 center. The exact amounts will vary by position and player quality of course, but the basic idea is fairly intuitive—teams save cap space by hitting on draft picks at the right positions, and they can use that cap space in free agency on better players at other positions that they don’t (or can’t) fill through the draft.

Teams realize this, which probably helps explain why some high value positions are drafted disproportionately in the first few rounds of the draft (as shown in Figure 1).

But drafting positional value also depends on some other assumptions.

One built-in assumption is that players drafted in round 1 are likely to be better than players drafted in round 2 (and so on). Put another way, players drafted higher are more likely to be good. That makes sense, and if you believe (as I do) that NFL teams are collectively good at evaluating talent, it’s a reasonable assumption.

There’s also an assumption that teams will “hit” on draft picks at about the same rate regardless of position. If you could identify top 10 centers much more often than top 10 edge rushers, for example, it would eat into the value proposition of drafting edge rushers more often and earlier than centers. But that’s a tough question to assess without looking at how teams and draft analysts rate individual players. Perhaps I’ll look into it more down the road, but for now, it’s a bigger project than I want to take on in this post.

A third assumption is that prospect quality at each position follows a relatively similar pattern. We would expect round 1 players to be better than round 2 players, round 2 players to be better than round 3 players, and so on and so forth—but what if the changes in player quality by draft round change at different rates for different positions? You can easily imagine a world where round 1 quarterbacks are great but round 3 quarterbacks basically never see the field—after all, only one QB plays at a time—but that’s much harder to imagine for a deeper position like cornerback, where 5-6 players might see playing time in a game. So I wanted to check into it here.

Draft Round vs. Production

You can imagine a variety of ways to evaluate how different positions compare with respect to performance by draft position. You could look at how many All Pro teams or Pro Bowl teams players make, you could look at counting stats like passing yards or receiving yards relative to their position, you could look at all-encompassing metrics like individual DVOA. Whatever measure you choose, they’re all going to be imperfect, especially given the wide variety of roles in football. Measuring players based on yards or touchdowns alone usually won’t work when more than half of the positions on the field will never accrue a yard or score a touchdown. So I wanted to pick a metric that is theoretically applicable to all 12 positions I cared about, and where it was reasonably possible to get the relevant data (with apologies to metrics Pro Football Focus grades, which are a pain in the butt to compile). Lucky for me, Pro Football Reference has a custom performance metric called weighted career approximate value that they have calculated for players drafted in the last 10 years (my focus) and more.

Pro Football Reference gives a full description of the approximate value (AV) metric here, but in essence, it is designed to get at the value of a particular player based on their contribution to their team’s offense or defense given the number of points scored or given up by the team, the fact that there are 11 players on the field at a time per team, and the fact that different positions contribute in different ways. The metric assumes a total number of points for a team’s offense (or defense) based on how many points the team scores (or gives up) compared to an average team, and then apportions some of those points to various position groups like the offensive line, rushers, receivers, etc., and then divvies those points up to the various players on the field. It also appears to incorporate some looser elements, such as whether players made Pro Bowls, particularly for positions that lack obvious statistical metrics like offensive linemen. It is, in effect, a composite metric designed to look at a player’s overall contributions given the context of the team they play on.

Weighted career AV (wAV) is a derivative of AV, but it looks at the total AV generated by a player over the course of their career and weights things in favor of their peak performance season (100% for the player’s best season, 95% for his second best season, 90% for his third best season, and so on). The effect of the weighting basically means that player quality is based on their athletic peak, and not weighed down as much by down seasons that may be the result of injury or their eventual career decline, but it does favor players with high peaks compared to players with sustained quality play at a lower peak. For my purposes, that’s fine. Even though wAV and AV are imperfect metrics, but they are readily available and I was able to pull them for every player in the 10 year draft pool that I looked at. Perhaps in a future post I will look at other advanced metrics like individual DVOA or Pro Football Focus grades, including as a point of comparison, but for now, wAV and AV will have to do!

Anyway, because Pro Football Reference’s wAV metric already incorporates positional differences, it shouldn’t be used to reliably compare players at different positions. That’s fine, no stat can be used for everything. While baseball has metrics like wins above replacement (WAR) that are great for that type of comparison, football’s diversity of roles and stats makes it less amenable to such all-encompassing metrics, so there isn’t anything perfect available. wAV doesn’t really fill the “WAR” role, but it can be useful to compare players within a position group (QBs to QBs, for example) while also controlling, at least somewhat, for differences in quality of offenses and other players on the team. Since I wanted to compare how players drafted early in the draft compare to players drafted later in the draft at the same position, and to see whether those differences are similar or different across positions, I had to play around with the stat a bit.

Specifically, I used the draft round, position, and wAVs for the relevant positions (quarterbacks, wide receivers, tight ends, running backs, offensive tackles, offensive guards, centers, edge rushers, defensive tackles, linebackers, cornerbacks, and safeties) to calculate the average wAV of players drafted in each round (1 through 7) by position. I used the average for each round because I wasn’t super concerned about capturing any individual player profile. If someone tells me I really ought to be looking at the median player in each round to capture an actual person, or that I ought to take the average wAV overall (rather than per season), maybe I’ll do so down the road. Also, while you would expect there to be differences in player/prospect quality at different draft slots within a particular round, the dataset I was working with probably isn’t big enough to go to that level of granularity.

Regardless, here’s what you get:

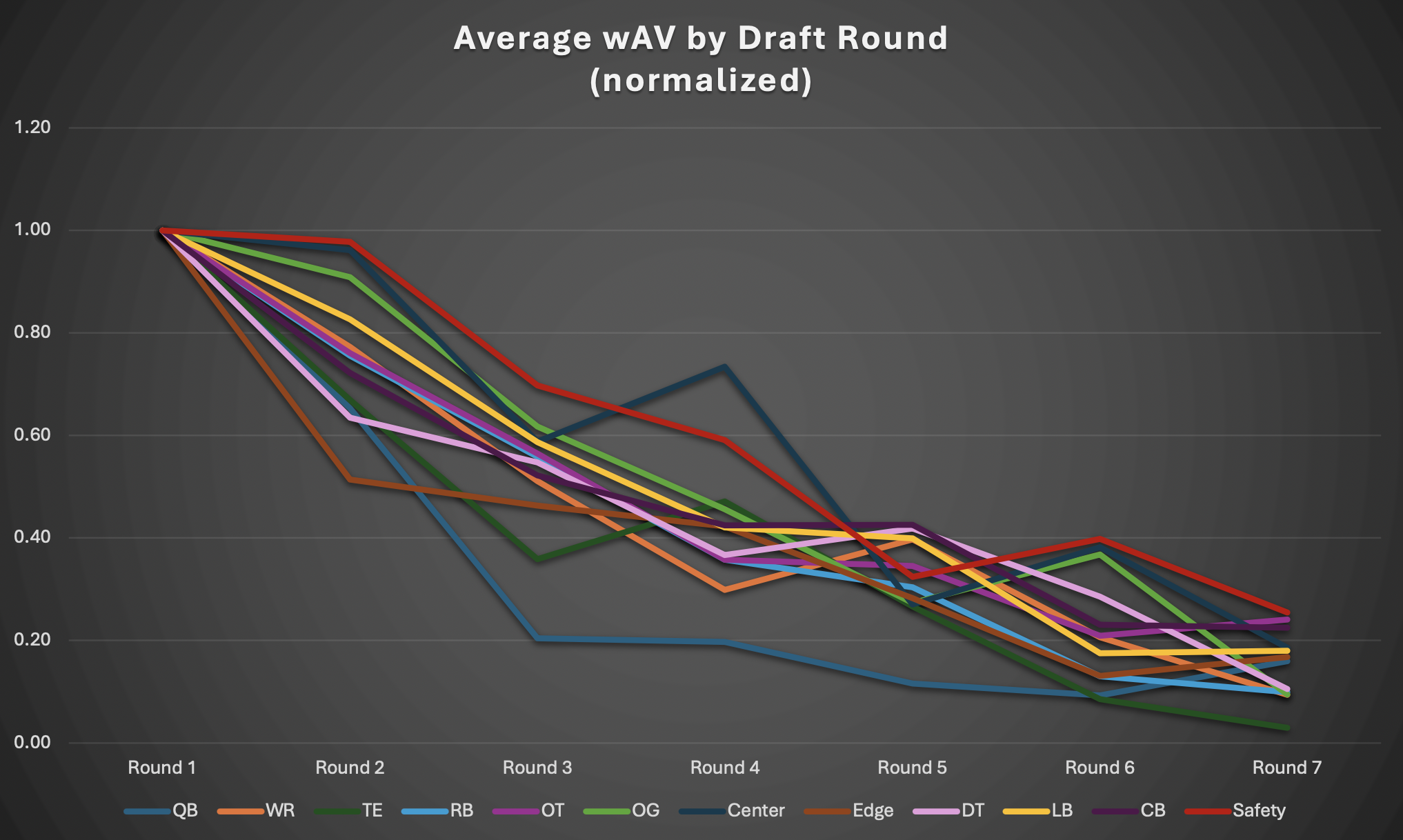

[Figure 2]

As you can see from Figure 2, on average, Round 1 picks perform better than later round picks regardless of position. But you can also see that the Round 1 wAVs are all over the place for different positions—for example, quarterbacks and running backs have relatively high Round 1 wAVs compared to cornerbacks and safeties (they all converge to zero in the later rounds, which makes sense given players drafted in the later rounds are less likely to have long, successful careers in the NFL).

That might be true, or it could simply be the result of how wAV is calculated (Pro Football Reference’s description of wAV makes clear that it is calculated differently for each position). Looking at the chart, I was skeptical that running backs were anywhere close to so valuable, so I wanted to make some adjustments to avoid simply capturing issues with the wAV metric being used. I decided to fix the starting points for each position around a consistent figure—the Round 1 average for each respective position. In other words, I set the Round 1 average to 1, and compared subsequent round averages to that figure. The effect is that QB wAVs get compared only to other QBs, edge rushers only to edge rushers, and safeties only to safeties, etc. That way, we can see how each position’s average wAV changes by round without having to worry too much about the differences in how wAV is calculated by position (it’s still baked in to an extent, but this is better).

The chart below shows the updated data, which I think is a bit clearer—it also shows the changes in player wAV by round for each position on the same scale, so cross-position comparison is more feasible.

[Figure 3]

Of course, this isn’t to suggest that all positions start off with the same round 1 value. It’s still a little messy given the 12 positions shown on one graphic, but I like Figure 3 because it lets you see how the various positions compare on a similar scale.

For convenience, to show how each position changes by round, I’ve also included individual charts for each that show the same data in slightly easier-to-see bar chart formats below (figures 4, 5, and 6).

[Figure 4]

[Figure 5]

[Figure 6]

Given this is still a small-ish data set—remember, we’re looking at 10 years of drafts and somewhere between 80 and and 324 players drafted at any given position—it’s important not to read anything too dramatic from these charts. But there are a few general things that are reflected.

Surprise, Surprise! Good Quarterbacks Go Early

The most notable thing to me is the dramatic cliff that QBs seem to hit, both after the first round and again after the second round. QBs drafted in the second round are, on average, posting career wAV totals that are 35% lower than first round quarterbacks. And QBs drafted in rounds 3-7 are basically just a crapshoot—it barely makes a difference at all which round you draft them in, chances are they won’t be good. [Special shout out to Brock Purdy for basically single-handedly propping up the 7th round QBs in this data set.].

This trend makes a ton of sense given what conventional wisdom (and Figure 1 above) says about quarterbacks: they’re disproportionately valuable, and teams will reach to draft quarterbacks in the first round.

Coupled with the fact that quarterbacks are the highest value position in terms of compensation, the obvious conclusion is that teams are correct to use early draft assets on quarterbacks if they think they can play in the league. The chances of finding someone reliable after the first round drop off markedly, and after the second round, they drop even further.

Edge Rusher Production Falls Off Quickly After Round 1

I was pretty surprised at how huge the drop-off was for edge rusher performance outside the first round. On average, second round edge rushers produce just over half the wAV of their first round counterparts (51%), a full 12 percentage points bigger of a drop off than the next closest position, defensive tackle. That was unexpected enough that I went back and looked over the full list of 44 second round edge rushers and it makes some sense at a glance. The group is headlined by a few standouts with pretty successful careers like DeMarcus Lawrence and Preston Smith, but it also has a fair number of guys who flashed for a year or two and have otherwise not been consistent like Randy Gregory. Compare that to Round 1 (52 players), which has those same types of players plus multiple truly elite players in Khalil Mack, Nick Bosa, TJ Watt, and Myles Garrett (among others), and stand-out young players like Micah Parsons, Aidan Hutchinson, and Will Anderson. It certainly seems like the studs at edge are identified quickly by teams and pounced on in the first round.

Even though there’s a decent drop off after the first round, average production doesn’t change a ton between rounds 2 to 4. This could suggest that players who obviously have high-level NFL talent get identified properly and go in the first round, but that teams aren’t as good at sussing out the next tier of player who may be missing some ideal traits or need time to develop. It could also just mean there are a lot of players with below first round talent, so they can’t all go in the second round.

Regardless, the implication is that teams probably should focus on the first round if searching for top-end pass rushers. When you factor in that edge rusher is an extremely expensive position to fill in free agency, and that teams draft a high proportion of edge rushers early in the draft, the conclusion is even stronger. That said, teams probably should still be willing to draft edge rushers in rounds 2-4 based on their production—and given what we could distill from Figure 1, that’s exactly what they seem to do.

Defensive Tackles Also Drop Off After Round 1, But There’s Solid Middle Round Talent

After edge rushers, the biggest drop-off following round 1 is for defensive tackles, where the average wAV drops 37% in round 2. Once again, this is partly due to a handful of stellar defensive tackles who’ve been drafted in the first round in the last ten years, headlined by future Hall of Famer Aaron Donald as well as Jeffery Simmons, Dexter Lawrence, and Quinnen Williams.

But unlike with edge rushers, the talent level at defensive tackle appears to level off a bit longer. For edge rushers, after a big drop off after round 1, average wAV stayed pretty flat from round 2 to round 4. For defensive tackles, the decline isn’t quite as steep initially and things don’t stay quite as even, but the average wAV in round 5 stays at over 40% of round 1 (compared to 28% for edge rushers). In other words, there has often been useful players still available in the fourth and fifth rounds in drafts, which is relatively deep.

The relatively big drop-off in production from round 1 to round 2 amongst DTs runs against how teams appear to actually draft the position (Figure 1). Teams don’t seem to prioritize drafting DTs in round 1 or round 2 compared to other positions, even though there’s a big drop-off early and it’s the 4th most valuable position in terms of salary cap spending. That suggests the potential to find good value in drafting first round defensive tackles.

Little Advantage Drafting Interior OL, LB, and Safety Round 1

The charts for offensive guard, center, linebacker, and safety are kind of interesting. What stands out is how small the apparent advantage is of drafting these positions in the first round versus the second round. For centers, guards, and safeties, you’re talking about less than a 10% drop-off in average wAV; for linebackers, the drop off is a little bigger but still relatively small at 17%. This makes some sense if you think about the relative value of these positions on the free agency market. Generally, these are positions you can fill reasonably cheaply in free agency (though that is becoming less true for offensive guards), so seems teams aren’t going after talented players at these positions in the first round. That’s backed up by the actual draft results from Figure 1, which show between 6-9% of players for these positions being drafted in the first round.

Center and safety talent also looks to stay reasonably high even through the third and fourth round. There just isn’t the same drop-off in average wAV compared to the other positions, it’s much more gradual. For centers, this might be explainable by the fact that it’s a single position, so teams don’t need to draft tons of players at the position. That explanation doesn’t make as much sense for other positions, though, like with safeties and linebackers. For those positions, it’s possible that teams have a deeper pool of players to pull from—in fact, you often see NFL safeties and linebackers come from other positions at the college level, especially players coming from FCS programs.

I suspect part of what’s happening here is that teams are doing a reasonably good job of appropriately valuing these positions. They’re easier to fill in free agency, so teams don’t want to spend their most premium assets on these positions. But after the first round, the performance curve seems to be more similar to other positions.

WR, OT, and CB—All “Lower” High Value Positions In Free Agency—Follow A Similar Pattern

It’s interesting that wide receivers, offensive tackles, and cornerbacks seem to follow a similar path in value-decline-by-draft round. Here’s the percentage of first-round average wAV for each position for rounds 2-6:

Round 2: WR 77%; OT 76%; CB 72%

Round 3: WR 51%; OT 56%; CB 52%

Round 4: WR 30%; OT 36%; CB 42%

Round 5: WR 40%; OT 35%; CB 43%

Round 6: WR 21%; OT 21%; CB 23%

Round 7: WR 9%; OT 24%; CB 23%

Obviously round 7 wide receivers drop completely off, so stay away from them!

I wonder if this trend is roughly what you’d expect from a “normal” high value position (quarterbacks are definitely funky, and it looks like there really is a bigger drop-off for edge rushers and defensive tackles before a slow-ish taper). It’s a relatively consistent and probably reasonable decline for each round, with some hiccups of course. The drop-off from round 1 to round 2 isn’t nearly as stark as with QBs, edge rushers, and DTs, which makes a bit more sense intuitively—it’s not as though second round picks are seen as chopped liver by teams and draft analysts, many of them are considered high-level talents that need more development early on. At the same time, there is a clear difference in average performance between the first round and second round groups at these three positions, which is what you’d expect. For guards, centers, and safeties, it’s definitely weird that there is basically no real drop-off between round 1 and round 2.

It’s also worth noting there are more wide receivers and cornerbacks drafted in the last 10 years than any other position (324 and 322 respectively). So it would make some sense that data for those positions would be less prone to noise. On the other hand, you also see teams regularly going 4 or 5 deep at these positions in games, so even late-round draft picks are probably going to see the field for meaningful time and contribute.

Gut Check With Games Played

I’m not totally convinced that Pro Football Reference’s wAV metric is all that reliable, so it’s hard to know how valuable any of the inferences above are.

As a gut check, I wanted to find some other relatively simple, easy to obtain data to at least see if the trends above make conceptual sense, beyond applying general draft trends that I’ve seen from watching the draft every year myself and reading a lot of draft coverage (a truly preposterous amount).

The easiest thing I could think of is whether the number of games actually played changes at different rates for different positions based on draft round. For example, the wAV analysis above suggests there isn’t a huge difference between centers and guards drafted in the first round versus the second round, but do first round centers and guards play a similar number of games to second rounders? If that matches the wAV trend, I’ll be more inclined to think of wAV as a useful proxy for performance when looking at draft picks by round. In addition, looking at games played has the added benefit of incorporating subjective views of NFL teams regarding how their draft picks perform, as we can assume that teams like to play good players more often (probably? I’ll disregard a couple teams perhaps…go ahead and fill in who).

Figure 7 shows the average number of games played for players drafted in rounds 1-7 by position. Figure 8 shows the same information, but as I did with Figure 3 above, I set the average number of games played by first round picks at 1 and scaled the data accordingly so you can see the different trends together (I didn’t dive into this, but some positions have longer careers than others due to the nature of football—I wanted to look at the data without worrying too much about that).

[Figure 7]

[Figure 8]

Without diving too much into the details, the rough check of wAV versus games played actually looks pretty decent for wAV. You see some of the same trends.

For example:

There’s an enormous drop-off in average games played by quarterbacks drafted in round 2 versus round 1, and an even steeper drop-off after that. You can be pretty confident if you draft a quarterback in rounds 3 to 7 that they won’t play a lot, as they’re probably a full-time backup.

Safeties and linebackers drafted after round 1 continue to play a relatively high number of games compared to other positions. There’s some lumpiness in the data (round 2 linebackers apparently play a lot, and round 5 safeties apparently don’t get on the field much), but it’s pretty consistent with what we saw from wAV.

Centers also seem to play a high number of games, but there’s a weird dip for round 3. Given they’re the smallest group in terms of total numbers—only 14 centers were drafted in round 3 in the last 10 drafts—I’m not reading much into it.

Wide receivers and cornerbacks seem to follow a common trend again, and it looks like they could be the most representative. Offensive tackles depart a bit from them, however.

Other things don’t show up:

Edge rushers look to be following basically the same downward trend as the other positions—if you draft them later, they’re less likely to play as many games. But there isn’t a dramatic drop-off after round 1 like we saw for wAV. That doesn’t necessarily mean the trend showing up in the wAV analysis was wrong. For example, most teams play at least 3-4 edge rushers per game, so it’s possible that underperforming players still see the field enough to register. But it’s worth looking into a bit more.

Guards appear to suffer a pretty stark drop-off in average games played after round 3. We didn’t see a similar drop-off in the wAV analysis. It could be noise? No real obvious reason jumps out to me.

Let me know what else you see.

Sign-Off

That’s it for now! Let me know if you have any observations or thoughts in the comments or by email at duncan@thesportsappeal.com. I’m happy to look into more depth on any position!

NFL Pre-Draft Thoughts: Positional Value

Hi everybody, I’m back again with a new post about the value of different positions and how it affects the NFL draft. Setting aside quarterbacks, what positions are most valuable? And how should that impact how teams think about who to draft, especially in the first couple of rounds?

Happy Sunday!

The NFL Combine wrapped up this weekend, so we are fully into NFL draft season. No surprise then that I’m seeing tons of conversation about the upcoming draft in April, including mock drafts, player projections, and content about team needs. That’s awesome for people like me that want to geek out over football, and you can easily spend hours (days? weeks?) pouring over every little nuance of potential roster moves. But there’s often something missing from a lot of the content I come across, specifically the importance of positional value and the cost of alternatives.

At a high-level, positional value is pretty straight forward and people get it intuitively: setting aside the talents of individual players, some positions generally have more value to teams than others. For example, it’s axiomatic that quarterbacks are more important in football than players at other positions, and it’s almost become dogma that left tackles are critical and that running backs should never be drafted early. Those conclusions make sense in the current NFL, but they don’t always provide enough information to weigh the relative values of NFL positions in general.

So, I want to use this post to talk about a pretty simple but powerful approach I like to use for understanding how to value the various position in the draft: who do you have to pay up for in free agency? If the position is expensive (especially at the top of the market), that strongly favors drafting it early.

Every year NFL teams dole out contracts in free agency, effectively putting a price on different players at different positions. That information is the purest form of price discovery that exists in the league since the draft isn’t a free market (worse teams get better picks), trades are much harder to measure when multiple players are involved, and undrafted free agents typically sign for the minimum. Thus we can use player contracts as a strong heuristic for how valuable each position is. The overall market still dictates the replacement cost for a particular position, regardless of whether an individual team has different views of positional value. Similarly, by looking at the broader market of player contracts, we can mostly ignore differences in perception about individual talent.

This approach isn’t anything unique that I’ve come up with, and I believe most teams do something like this when coming up with organizational draft philosophy. But it’s still a really useful exercise to go through because it forces you to think how much value you gain or give up by using draft picks (especially high draft picks) on particular positions.

The Process

Let’s start with the data on NFL contracts.

Every NFL player signs a contract with compensation comprised of base salary and often bonuses. It’s pretty common for NFL contracts include an upfront signing bonus (paid immediately) on top of base salaries (paid out weekly over each season of the contract) and future bonuses, too. Although some players—largely starters—get a portion of their future salary/bonus compensation guaranteed, typically NFL teams can release a player and avoid paying them future amounts. That means that assessing the “value” of an NFL contract can be a bit tricky.

To get around the valuation problem, I want to look at a couple different ways to value NFL contracts. The first is to look at the average annual value (AAV) of each contract—basically the total compensation divided by the number of years called for in the contract. The second is to look at the total guarantees in a contract. Looking at AAVs is the easiest short-hand, but I want to make sure there isn’t something totally unusual happening with guarantees (for example, some positions getting guarantees and others not). Plus, Overthecap and Spotrac have this kind of information readily available and I’m all about convenience.

Using data from Overthecap, I pulled together a list of all players league-wide under contract as of February 26, 2024 by position. I used positional groupings from Overthecap, too, except I excluded positions that aren’t common to all teams (fullbacks) or are purely for special teams (kickers, punters, etc.). The groups are as follows:

Offense:

Quarterbacks

Running backs

Wide receivers

Tight ends

Left tackles

Right tackles

Left guards

Right guards

Centers

Defense:

Interior defensive linemen

Edge rushers

Linebackers (excluding 3-4 outside linebackers)

Cornerbacks

Safeties

[The positional grouping for each player can be debated sometimes, particularly for positions like left vs. right side on the offensive line or between interior defensive linemen and edge rushers. I looked over how Overthecap grouped them and it seemed reasonable to me, though, so I didn’t dwell on it.].

The compensation data for the position groupings we care about covers 2,296 players (it’s available here, or you can email me if you want a copy of the spreadsheet I pulled the data into).

Looking at the data as a whole, it jumps out right away that the NFL pays top-tier players well and the lower-end players very little. At the high end, 19 players have contracts with AAVs of $30 million or more. On the other end of the spectrum, the vast majority of players—over 70%—are on contracts with AAVs under $2 million (for reference, the league minimum for 2024 ranges from $795,000 to $1.21 million depending on seniority); about the same number have less than $2 million in salary guarantees, too.

This disparity makes some sense once you consider that NFL teams have 53-man rosters (plus practice squads) and there is a distinct need to employ backups, special teamers, and injury replacements.

Practically speaking, it also means that at the bottom end of the pay scale, it’s basically impossible to draw meaningful conclusions about positional value because all the contracts start collapsing toward the league minimum salary. To avoid that issue, I’ve basically ignored lower-end contracts for purposes of this article (trust me, it doesn’t make a difference).

I also want to quickly point out that obviously not all positions are the same in terms of how many players you need to play them. Only 32 quarterbacks can start in the NFL, but most teams effectively “start” three wide receivers, two or three cornerbacks, two or three linebackers, two safeties, two edges, and two interior defensive linemen. That obviously has a material impact on the market—there are more wide receivers and cornerbacks that actually play than there are quarterbacks (before accounting for backups). That reality should be priced into player salaries, but it’s worth keeping in mind.

Where Does the Money Go?

The chart below shows averages of the Top 5, Top 10, Top 20, Top 30, and Top 50 highest AAVs by position. As a cautionary note, these aren’t perfectly apples to apples comparisons for the top 50 column in particular, as there are different numbers of players at different positions.

[Figure 1]

The next chart shows the average total guarantees by position for the same groups (Top 5, Top 10, Top 20, Top 30, and Top 50).

[Figure 2]

Something leaps out immediately: Quarterbacks are crazy valuable!

That’s not really a surprise to anyone. In fact, they’re so valuable that they distract from what’s going on with the other positions. So let’s take as true that quarterback is the most valuable position in football (at least based on how NFL teams pay them) and take it out of consideration for now.

We can re-work the chart to exclude quarterbacks—here’s the same data without quarterbacks shown:

[Figure 3]

And here’s a line graph based on the same data (rounded), which makes it a bit easier to compare the positions against one another generally. I find the line graph a little misleading, but it’s a useful way to compare the positions at the different levels of extraction (top 5 to top 50).

[Figure 4]

Figures 5 and 6 are similar to Figures 3 and 4, but but by Total Guarantees:

[Figure 5]

[Figure 6]

These charts (Figures 3 to 6) are a bit easier to follow without quarterbacks mucking things up with their giant contracts.

I'm also including a table with the rounded dollar figures in millions (Figure 7) so they’re easier to see—you’re welcome to trace the bar charts if you like.

[Figure 7]

Alright, that’s out of the way.

This information is helpful to rank positions by value.

When looking at position AAVs, a pretty clear ranking shows up at the top of the market (top 5 and top 10):

Edge rushers

Wide receivers

Interior defensive line

Left tackles

Cornerbacks

Right tackles

Linebackers (T-7)

Safeties (T-7)

Tight ends (T-9)

Right guards (T-9)

Left guards (T-9)

Running backs

Centers

But if you look at top-market total guarantees, another order pops up—I’ve put in bold red text the positions that moved down and bold green text the positions that moved up relative to the AAV order:

Edge rushers (massive advantage over every other non-QB position)

Wide receivers

Cornerbacks

Interior defensive line

Left tackles

Right tackles

Linebackers

Safeties (T-8)

Tight ends (T-8)

Left guard

Right guard

Centers

Running backs

These generally rankings seem to generally stay roughly the same even as you expand to bigger shares of the market (top 30 and top 50 players at each position), but it’s again worth noting that the number of players that actually see the field for a given position (without injuries) starts to have a bigger impact once you get past the top 20-30 players at the position. This is most apparent with cornerbacks passing left tackles for AAV at the top 30—assuming health, only 32 left tackles start league-wide on any given Sunday, whereas you’re going to see at least 64 cornerbacks play each week (and probably closer to 96, since almost every team plays a lot of nickel defense at least). That same thing probably also explains why right guards, left guards, and centers all start to lump together after the top 20—at a certain point, you’re talking about replacement-level starters or backups at relatively low cost positions.

I was also curious and looked at the same AAV and total guarantees compensation data for each position sorted by the percentile ranking within the position itself. The data here isn’t averaged out by top 5, top 10, etc., it’s just the straight data. I also took out anything below the 75th percentile as the compensation starts to veer off toward the league minimum and just collapses on itself. I think it tells a pretty similar story, but I’ll post it anyway so folks can see (Figures 8 and 9 below). The major caveat here is that the number of players at each position has a HUGE impact on the bar charts below—offensive line at every level looks way more expensive, but that’s because there are the fewest players under contract at those positions. The data set I have covers 94 left tackles, 99 right tackles, 93 left guards, 77 right guards, and 70 centers, while there are 307 wide receivers, 277 cornerbacks, 234 interior defensive linemen, 231 edge rushers, 219 linebackers, 182 safeties, 159 running backs, and 153 tight ends. It skews the percentile comparisons a lot. For example the 75th percentile center is #18 in the league, whereas a 75th percentile wide receiver is #77. Take these with a grain of salt.

[Figure 8]

[Figure 9]

Lessons for Drafting

So let’s get to some lessons we can draw from the information above about the draft.

Edges and wide receivers are ideal early draft targets.

Excluding quarterbacks, the top edge rushers and wide receivers get more money per year on average than anyone else and get the most in guarantees. That premium cost shows up at the top end of the market clearly, but it continues even as you move downward. These are obviously high-value positions in the modern NFL, where the passing game is so important, but the substantial distance between their average pay and guarantees compared to other premium positions like cornerback and left tackle is pretty apparent, especially at the very top of the market.

The value of finding high-end talent at these positions in the draft is absolutely massive. First round rookies get signed to 4 year deals with a 5th year team option, so locking in All-Pro level talent with a first round pick at edge rusher or wide receiver can create a huge amount of surplus value to the team compared to getting the same level of talent at other positions.

I also want to flag something that came up as a bit of a surprise to me. Edge rushers get absolutely massive total guarantees in the veteran market compared to every other non-QB position (even wide receivers). If you look at Figures 5 and 6, it jumps out immediately—they’re getting $30 million or more in guarantees than any other position. While edge rushers may only make a couple million more per year than wide receivers at the high end of the market, that difference in guarantees actually is a major, major difference for teams who need to worry about the risk of injury.

If you assume (as I do) that over time and on average, higher draft picks are more likely to end up being high-end NFL players, there’s no doubt that focusing on edge rusher and wide receiver for team’s premium draft assets (first round and second round picks) is a good bet.

On top of that, from a practical perspective, every team has to have at least three capable wide receivers and edge rushers. Offenses frequently run 3 WR sets and edge rushers really can’t stay on the field the entire game no matter how good they are. So even if you don’t get a player who turns out to be a top-of-market talent, landing guys who can play even at a back-end starter level has incredible financial value.

Don’t Forget the Beef (At Least On Defense)

You never hear anyone talk about defensive tackles as a premium position, pretty much ever. Occasionally, reporters and prognosticators will talk about how a couple interior D-linemen like Aaron Donald, Chris Jones, or Quinnen Williams are valuable because they can pass rush like ends, but that’s really understating things hugely. Even guys who are thought of more often as space eaters like Dalvin Tomlinson and DJ Reader are making $13-14 million per season on average. In fact, at every level of the market, defensive tackles are getting paid more than offensive tackles (left or right side) and corners, which isn’t the prevailing wisdom amongst pundits and draft watchers.

Also, like with edges and wide receivers, most teams have to regularly play three or more defensive tackles every game. These guys are big and asked to do a lot athletically—they need breathers, more than most positions. Having extras makes sense. And even if a defensive tackle doesn’t turn out to be an All Pro, having a top 50 player at the position is more valuable than getting a comparably talented offensive lineman, who will inevitably be a backup.

Be Cautious Drafting Right Tackles Early

The whole league values left tackles more than right tackles, since they’re the blindside protectors for right handed quarterbacks (though obviously there are a number of lefties in the NFL now like Tua Tagovailoa), so it’s no surprise that LTs are generally paid more than RTs per year. But I was surprised by how much of a gap shows up at the middle- and lower-end of the market for starters.

Amongst the top 10 players at each position, left tackles are paid on average about 13% more than right tackles. But that gap widens substantially when you look at the top 20 and top 30 at each position, where the pay difference is about 26% and 25% respectively. Using a high pick on a right tackle can be fine (it’s about middle of the pack in terms of positional value) if you end up with a high-end starter, but if you end up with a back-end starter it’s a lot less efficient financially that drafting a left tackle.

Common Wisdom Is Sometimes Spot On

Football followers all know this by now, but the league does not value running backs. The league’s highest paid (and presumably best) running backs are getting paid comparably to the 50th best edge rushers and wide receivers, or the 30th best corners and left tackles. Forget whether it’s true that you can find running backs late in the draft—simply paying for a running back in free agency is a cheap alternative to drafting one early. The opportunity cost of using early picks on running backs is far too high to justify in most situations. You’d have to believe that a given running back you draft will be a top 5 player at his position versus believing that an edge rusher you draft would be a top 50 player for it to make any sense.

Teams Seem to Know Centers Are Cheap, But Does Anyone Else?

I keep seeing mock drafts putting multiple centers in the first two rounds—usually Jackson Powers-Johnson from Oregon, Graham Barton from Duke, and Zach Frazier from West Virginia. That’s not a good use of draft capital, as centers are one of the easiest positions to fill in the open market, where a starting caliber player (top 20) is actually cheaper than even running backs. I never hear analysts talk about this, but it’s a useful lesson. DON’T WASTE EARLY PICKS!

A similar thing can be said for guards even though the top of the market is more robust. If a team thinks a guard will be a top 5 player at his position, it could be worth using early draft capital on him—any other outcome, and it’s similar to drafting a running back or center. It’s not a good position to use early draft capital on.

Safeties, Tight Ends, and Linebackers Are Fine, I Guess?

Perhaps the least interesting groups here are safeties, tight ends, and linebackers. Their comp seems to track each other reasonably closely and they land pretty squarely in the middle of the value stack. As a result, drafting them early isn’t the highest use of resources, but it’s not as inefficient as drafting RBs or interior offensive lineman like guards and centers. The “best case” outcomes really pale in comparison to edges, wide receivers, interior DL, and left tackles in terms of potential value though, so it’s probably best to avoid using first round picks on these positions even if you think the player is going to be great—just pay somebody in free agency instead.

Wrap Up

I really like looking at positional drafting based on market cost. It’s simple, intuitive, and reflects the real world value of the position. Teams always have the option of filling roster holes with free agency instead of the draft, so they ought to be thinking about how much it costs to do so when evaluating picks. Of course there are other interesting ways at looking at positional value (Pro Football Focus has a fun one looking at their wins above average stat), but most of them tend to rely on imperfect comparisons that may not reflect what’s actually happening in the league, so I tend to put less weight on them. And while obviously teams need to think about things like draft slot and their own roster, scheme, and strategy—those are important!—they always have to live by the rules of the market they exist in, since roster needs change, coaches get fired, and prevailing wisdom changes. Looking to the alternative cost of filling roster holes, besides draft picks, is a good place to start.

Chargers 2024 Salary Cap

I’m back this week after a vacation and the Su er Bowl to take a look at the upcoming Chargers offseason.

Things are looking up for the Bolt Gang after hiring new head coach Jim Harbaugh and new general manager Joe Hortiz in January, but there’s a lot of work to do on the roster this off-season. The Chargers need, to clear almost $70 million in cap space to get under the cap and manage their roster going into next year.

I’ve seen a lot of reports that this is “salary cap hell,” but that’s not really true. The Chargers have ways to get under the cap this year without just pushing off all of the salary cap challenges to the future. Some moves are going to be painful—the Chargers are probably going to lose some good players during the off-season—but the team definitely can still keep its most important players.

Check out this post where I dive into the details!

It’s been a bit since I’ve posted because I was on vacation and watching the Super Bowl. Sorry Niners fans, I was pulling for you. I’m back to it this week to take a look at the upcoming Chargers offseason.

Things are looking better in Los Angeles for the Chargers after hiring new head coach Jim Harbaugh and new general manager Joe Hortiz in January, but it’s been widely (accurately) reported that the Chargers are facing some big off-season salary cap challenges in deciding who to bring back and at what price.

I think a lot of the conventional wisdom in articles and reporting has gotten ahead of itself on the Chargers salary cap issues, so I wanted to go through them. The Bolts aren’t in a great situation with respect to the salary cap, but it’s definitely not “salary cap hell,” as I’ve heard it described by a few pundits. Depending on how the Chargers address contracts for just a handful of players, they don’t necessarily face long-term issues either.

Before diving into the Chargers specifically, I want to go over some basics about the salary cap, how players get paid, and how teams manage their rosters around the salary cap. The rules can be confusing, but they’re integral to how teams build their rosters—there’s no way to understand what a team is going to do in the offseason if you don’t have at least some familiarity with these issues—so it’s a good jumping off point. [There are some primers on this stuff if you want to really get the details—this one from Anthony Holman-Escareno at NFL.com is really thorough, though it covers the 2023 offseason. You also can dig into the CBA.]

I’ll jump right into it.

The NFL Salary Cap

The NFL salary cap rules are the bedrock of roster construction. They can be confusing, so I’m going to simplify things a bit where appropriate to hopefully make this more digestible (you can let me know in the comments if you want more details).

At a basic level, NFL teams have to fill their roster with players who are paid a combination of salary (paid weekly) and bonuses (paid at specified times). Players sign contracts for one or more years and for each year of the contract, the player has a “salary cap charge” that counts towards the team’s salary cap based on how much salary and bonuses the player is slated to receive that year, with some accounting nuances that I’ll describe more later.

The NFL salary cap is what’s known as a “hard cap,” meaning that the money teams pay their players in a given year cannot exceed the salary cap. In other words, player salaries and bonuses for the whole roster added together must fall below the cap. That’s different from the “soft” salary cap for the NBA, which I’ve talked about before, that has a dozen or more exceptions that allow teams to go over the salary cap. The NFL’s salary cap was set at $224.8 million this past season and it is projected to increase to over $240 million for 2024, though the final figure hasn’t been set yet. [Note: some projections, including OvertheCap.com’s, expect the salary cap to come in slightly higher, but I’m using $240 million for now because that’s the latest the NFL has indicated. There’s a good chance the actual cap number comes in a bit higher.]

Counting Team Salary

The way a team’s salary gets calculated for salary cap purposes is detailed and can be convoluted, but at a high level it’s fairly simple. You simply add up the salaries and bonus payments made to players on the roster for a given year, with some fairly simple accounting for discrete items. The components of a team’s salary can be thought of as the three buckets below:

Salaries for players on the roster;

Bonuses paid to players on the roster (this gets more complicated, but we’ll deal with the nuances later); and

“Dead cap” or “dead money” hits, which represent salary caps for players who are no longer on the roster but for whom the team still has to take a salary cap charge.

These components aren’t super confusing—teams have to count the actual money they’re paying to players in a given against the salary cap (salaries and bonuses), and they also have to account for money they already paid to former players as “dead cap” if that money wasn’t counted against the salary cap in a prior season.

The natural implication is that timing is important. When teams take cap charges for salary, bonuses, or dead cap depends on the team’s strategy, but they have to operate within the league’s rules.

Generally, the NFL counts player salaries—the amount they get per year in game checks—toward the team’s salary cap in the year the salaries are paid. If a player’s salary is $10 million for the season (and, for simplicity, we assume the player has no bonuses), the team’s salary cap charge for the player would be $10 million. There are some nuances for players with salary guarantees which I’ll discuss a bit later, but the basic rule is straightforward.

When teams take cap charges for bonuses depends on the type of bonus it is. For some bonus categories like signing bonuses, teams spread out the salary cap charges across the life of the contract—for those familiar with accounting, the team expense of the signing bonus is simply amortized on a straight line basis over the life of the contract. Most other bonuses, including things like roster bonuses (for being rostered as of a particular date), workout bonuses (for attending team workouts), and performance-based bonuses are charged against the salary cap in the year they are paid.

Dead cap hits typically result from a team cutting a player, trading a player, or a player retiring. The dead cap hit counts against the team’s salary cap for either the season in which player was cut/traded (or retired) or the following season, depending on the specific date the cut or trade occurred (June 1st is the magic day if you’re curious).

For any given season, all of those salary cap charges combined—salary and bonuses for rostered players and dead cap hits—have to fall below the salary cap.

Team Use of Cap Space

It’s also important to understand what NFL teams have to use salary cap space for because it governs how they think about managing their respective cap situations. I’ve talked about the first two items below, player compensation and dead cap, but the latter four are also important and often not top of mind for NFL observers:

Teams must pay the players on the roster (player salaries + bonuses).

Teams must account for “dead cap” hits for player cuts, trades, or retirements.

In connection with the NFL draft, teams must set aside some portion of salary cap space for players they select (how much depends on how many picks they have and, especially for first round picks, how high in the draft order they go).

Teams reserve some amount of salary cap space to sign new players in case someone on their roster gets hurt (this is pretty much guaranteed to happen at some point).

Teams may save a portion of their cap and use it as “rollover cap” for the next season—in other words, if a team has space below the cap, they can choose to “rollover” that space into the next season.

A bunch of other stuff! Practice squad player salaries, money paid in response to player grievances, off-season workout payments, and a host of other things are also lumped into the salary cap. These are generally small amounts (relatively) so I won’t dwell on them.

What Goes Into a Player’s Salary Cap Charge

The way that a salary cap charge for an individual player gets calculated is conceptually simple—it’s basically the sum of his compensation for the year plus a prorated portion of his signing bonus (the amortized bonus). A simple way to think of it is that the player’s salary cap charge for a given season is the sum of the following:

Base salary for the season. This is the player’s salary, which is typically paid out per game.

In-season bonuses. There are several kinds of in-season bonuses including roster bonuses (bonuses paid for the player being on a roster as of a specified date, like the start of training camp); workout bonuses (bonuses paid to incentivize players to show up for off-season or pre-season workouts); and per game bonuses (pretty self-explanatory).

Incentives. These are basically bonuses paid for a player hitting particular performance targets, like rushing yards for the season or total touchdowns. For salary cap charge purposes, these get wonky. There are “likely to be earned” incentives (LTBEs) and “not likely to be earned” incentives (NTLBEs), and they are treated differently for salary cap purposes. We don’t need to dive into the details here, so I’ll skip it for now.

Prorated signing bonus. Players usually get cash up front as a signing bonus when they sign their contracts. This cash is paid up front to the player at the time they sign their deal, but it is accounted for under the salary cap as though it were paid out in equal installments for each year of the contract.

For example, a player could sign a three year deal for a total value of $45 million, with $15 million paid as a signing bonus and $10 million in base salary for each year of the contract. The $15 million signing bonus would be accounted for as though it was paid in equal installments over the course of three years, or $5 million per year.

Prorated “restructuring” bonus. Restructuring bonuses are something that articles and media sometimes refer to, but they aren’t really a different category of bonus—it’s treated the same as signing bonus. These restructuring bonuses occur when when the team elects to pay some portion of a player’s salary in a given season as bonus (this is a pretty unique rule for the NFL, so I’ll discuss it more below). Rather than getting weekly salary, the player gets the money up front as a signing bonus, and the amount is then prorated over the remaining life of the contract.

To see how this works, let’s look at the same three year, $45 million total value contract with a $15 million initial signing bonus that I referred to previously. In Year 1 of the contract, the player actually receives $15 million in signing bonus and $10 million in base salary, $25 million in total, but his salary cap charge for the season is just $15 million—$10 million in base salary and $5 million in prorated signing bonus. In Year 2, the salary cap charge is once again $15 million, although the player actually gets paid only the $10 million in base salary (he already received the signing bonus at the start of the contract). Year 3 is the same as Year 3.

Now instead imagine that at the start of Year 2, the team decides to convert $6 million of the player’s base salary into so-called “restructuring” bonus. That $6 million bonus gets prorated for the remaining two years of the contract in the same way the original signing bonus was prorated over the life of the original three year deal. This time, the player still actually gets paid $10 million in Year 2, but $4 million is base salary and $6 million is paid as restructuring bonus. Thus his Year 2 salary cap charge is $12 million (instead of $15 million): $4 million base + $5 million in prorated signing bonus + $3 million in prorated restructuring bonus.

In Year 3, the player gets paid $10 million (all base salary), but his salary cap charge would go up to $18 million: $10 million base + $5 million in prorated signing bonus + $3 million in prorated restructuring bonus.

Teams Have Three Primary Ways to Address Cap Issues

There are three main ways that a team can reduce the salary cap hit for a particular player: (1) move on from the player, usually by releasing or trading them or if they retire, (2) “simple restructures” of the player’s contract, or (3) renegotiations of the player’s contract, which typically involves extending the contract in some way.

Moving On

Teams can move on from players in a few ways to save themselves cap room:

If the player’s contract is up, they are a free agent and the team can choose not to re-sign them;

The team can release a player to move on from their contract and avoid paying the player unpaid upcoming salary and certain future bonuses, subject to any negotiated guarantees in the player’s contract;

The team can trade the player away; or

The player retires.

For purposes of this post, I’m going to focus on player releases as the main way to “move on” from a player and avoid paying salary. This is because letting a player walk in free agency doesn’t really directly affect the salary cap situation—the player isn’t under contract and doesn’t count against the team’s cap anyway—and because trading away a player has similar implications for salary cap purposes as waiving them (setting aside whatever player salaries come back in a deal). Similarly, for cap analysis purposes, a player retiring functions mostly like them being cut, though there are some nuances based on when and why a player retires (e.g., whether the player retires for injury and how much time they have left on their contract, if any).

Teams release players by cutting them from the roster, which generally allows the team to avoid paying the player any unpaid upcoming salary (other than guarantees they may have specifically negotiated). Unlike in the NBA and MLB, the vast majority of NFL contracts are not guaranteed, so when team’s release players that typically ends any future obligations to continue paying the player after release. Teams also aren’t required to take salary cap charges for the unpaid, non-guaranteed salary and unpaid, non-guaranteed bonuses, so releasing players is often an effective way for teams to clear out cap space.

Some players negotiate for guaranteed or partially guaranteed salary or bonuses in their contracts, and those guarantees generally do have to get paid even if a player is released. Guaranteed salary or bonuses also do get counted as salary cap charges for the team, so the benefits of cutting a player with guarantees are much less significant for the team. As a result, players with salary or bonus guarantees usually aren’t going to get released—that’s why they negotiate the guarantees in the first place.

While teams don’t have to count any unpaid, non-guaranteed salary, bonuses (like roster bonuses or workout bonuses), or incentives to the player as salary cap charges when the player is released, signing bonuses are treated differently. As I noted above, signing bonuses are paid up front and amortized across the life of the contract. So when a player gets released—meaning the contract is terminated early—the future years still have prorated signing bonus cap charges. Those future cap charges don’t just disappear. Instead, the future cap charges for prorated bonus get “accelerated” and count against the team’s salary cap immediately. These aren’t cash amounts the team pays out upon releasing a player—it’s just on paper, the team already paid the money—but the NFL forces teams to account for those bonuses as “dead money.”

For example, the Chargers released cornerback JC Jackson midway through the 2023 season. As a result, they will have to eat over $20.8 million in dead money against their salary cap this year ($15 million of Jackson’s prorated signing bonus and just over $5.8 million of “restructuring” bonus) even though they won’t actually pay Jackson any money in 2024. [If you’re wondering why Jackson’s dead money hit comes in 2024, it is due to the timing of his release—he was released after June 1 of the 2023 season, so the dead cap hit is counted for 2024.]

Teams release players when they can save money against the cap and not generate huge dead money hits, since that dead money can’t be used on the rest of the roster that season (hence the name).

Simple Restructures

Simple restructures are often used by teams to manage their salary cap situation. As I’ve explained, an NFL player’s compensation in a given season can be broken up into (A) base salary and (B) bonuses. The NFL CBA allows teams to convert the majority of player’s base salary into signing bonus essentially at will (they can’t convert it all, as there are some restrictions like players having to make at least the league minimum salary for his seniority level).

Simple restructures are a valuable tool in salary cap management because they allow a team to create cap space immediately. Player base salary gets charged against the team’s cap for the year in which it is paid, but signing bonuses and “restructuring” bonuses are prorated across the remaining contract term—so by converting base salary to bonus, the teams can create salary cap space in the current season by spreading out the cap charges over multiple seasons.

Team’s don’t generally need to consult the players to do these kinds of simple restructures under the CBA. That seems weird, but there’s no real reason the players should care since getting paid earlier is generally favorable for them: they get paid the same amount at the beginning of the season as opposed to getting paid out over the course of the year in game checks. It’s just an accounting gimmick that lets teams move around what salary cap hit they take in a given season (base salary) versus what gets spread out over multiple seasons (signing bonus).

Extensions/Renegotiations

Teams can also renegotiate contracts with players, subject to some restrictions that aren’t super important for this post. Renegotiations can work a variety of ways, but it basically just means the team and player revisit the essential terms of the contract—the amount of compensation, the amount of guaranteed compensation, and/or the number of years the contract runs.

There are lots of situations when renegotiations can occur, but I’ll focus on a few common ones:

The team wants to extend the length of the contract to keep the player under contract longer.

The team wants to extend the length of the contract in order to spread out the prorated cap charges for the player’s signing bonus over a longer period of time.

The team wants to reduce the amount paid to the player, but would keep them around if they are willing to stay at a lower price—implicitly, this means the team would otherwise cut the player if they don’t take a pay cut.

In these situations, the team and the player will negotiate to change the terms of the contract to allow the team financial flexibility.

A lot of extensions just add years to the contract and the team and player negotiate what salary they will be paid in each year and how much will be paid up front as bonus (and prorated over all the years of the contract). These are pretty normal and function like contract extensions in other sports.

The NFL also allows another odd accounting gimmick where teams can negotiate to add “void years” to contracts. Essentially, void years are fake years added to the end of a contract for salary cap accounting purposes. The player will not play in these void years, and everybody knows that, but the void years extend the length of the contract and allow teams to spread out the cap impact of signing bonuses over a longer period because the void years get included as part of the contract term when amortizing the signing bonus.

As an example, a player signs a contract with a $12 million signing bonus for four years, with two void years at the end. For salary cap purposes, the signing bonus is prorated over six years (even though the player is only contracted to play for four), so the cap charge of the signing bonus is $2 million per year. Without the void years, the cap charge for the signing bonus alone would be $3 million per year.

Void years don’t allow the team to avoid cap charges entirely. When the real contract years end and the player is no longer going to play, the remaining prorated bonus cap charges accelerate and are charged to the team’s salary cap (assuming the player isn’t re-signed or extended). Thus, when the cap charges for the void years accelerate, the team winds up taking a big cap charge as dead money. This functions like a sort of balloon cap charge at the end of the contract, so it can be tough to manage—so some teams like to use void years as a regular tool to manage their cap while other teams just avoid them entirely (the Chargers haven’t used void years very frequently, but we’ll see what new GM Joe Hortiz prefers soon enough).

Now that we’ve eaten our vegetables, let’s get to the Chargers situation.

The Chargers Are WAAAY Over the Cap

At a glance, the Chargers look to be in a tough cap situation. According to Overthecap.com, the Bolts have about $270.8 million in salary cap dedicated to their 2024 roster (49 players out of 53 total roster spots) and $24.6 million in dead cap hits—meaning their overall team salary cap number would be about $295.4 million. Given the 2024 salary cap will be around $240 million, the Chargers look to be roughly $55.4 million over the cap right now. [I’m rounding numbers here for simplicity—there’s no need to be too precise given we’re working with several projections anyway. Overthecap uses $242 million for the expected 2024 salary cap.]

But things aren’t quite that simple.

For one, the basic cap analysis above doesn’t account for a few important things.

The Chargers still have four empty roster spots and they will eventually have to sign their 2024 draft picks. The Chargers have seven picks in the upcoming NFL draft, so they’re going to be adding up to seven players to the roster (barring trades, which can increase or decrease the number of selections they have in the draft). Assuming they stay at their current draft positions, the Chargers will need to pay the seven newly drafted players ~$14.4 million next season—the bulk of which will go to whomever they take with their first round pick. Since the Chargers have just four open roster spots, they would also get to cut three players on their current roster—likely guys who make the minimum of $795,000—which would save about $2.4 million in cap space. So we can assume the Chargers would need about $12 million to sign their 2024 draft picks and fill out the roster ($14.4 million minus $2.4 million).

The team also needs to reserve at least some space for potential injuries and miscellaneous cap charges. It’s hard to say exactly how much cap space the team will need for this, but we want to leave a reasonable cushion of about $10 million.

In addition, the Chargers were about $8 million under the salary cap in 2023 and can use that $8 million as “rollover cap” for 2024. In essence, that $8 million amount would get taken off of the team’s salary cap total for next season.