Kings NBA Trade Deadline (Part 2): In the Weeds On Trade Chips and Rules For Deals

[This is part two of a series of posts on the Kings ahead of the February 8 trade deadline. In part one, I wrote about some of the key issues that have crept up for the Kings so far this season, including issues on offense when De’Aaron Fox sits and on defense protecting the paint and three point line.]

The most exciting part about the trade deadline is imaging who your team might go get. Trade rumors, whispers about which players may want out, and hypothetical trades are all over the place this time of year, so it’s easy to get excited and jump right into playing with trade machines to build out your own hypos.

And honestly, who can blame you? Trade machines these days are pretty good! They’ll do most of the hard work for you. They have already listed out each player and their contract, identified draft assets held by each team, and figured out how to match salaries, all of which is critical to making any NBA trade work. Yet they still don’t do the harder work of figuring out how teams can protect against downside risk, address future cap issues, deal with looming contract decisions, and ensure roster flexibility. That part is still quite a slog.

Here, I’m going to go over what the Kings have to offer on the trade market, specifically current players and future draft picks, and I’ll try to flag the core, nitty-gritty issues that impact what can get done in a deal and the value of players and future picks.

So What Can the Kings Offer In a Trade?

The first thing that any team has to look at is what it has in the cupboard. Broadly speaking for basketball, there are two primary buckets: players on your roster and future draft picks.

The Players

On the player-side, the Kings have 14 players on the current roster, one player on a 10-day contract (Juan Toscano-Anderson), and three players on two-way deals so they can split time with the G-League Stockton Kings (Jordan Ford, Keon Ellis, and Jalen Slawson).

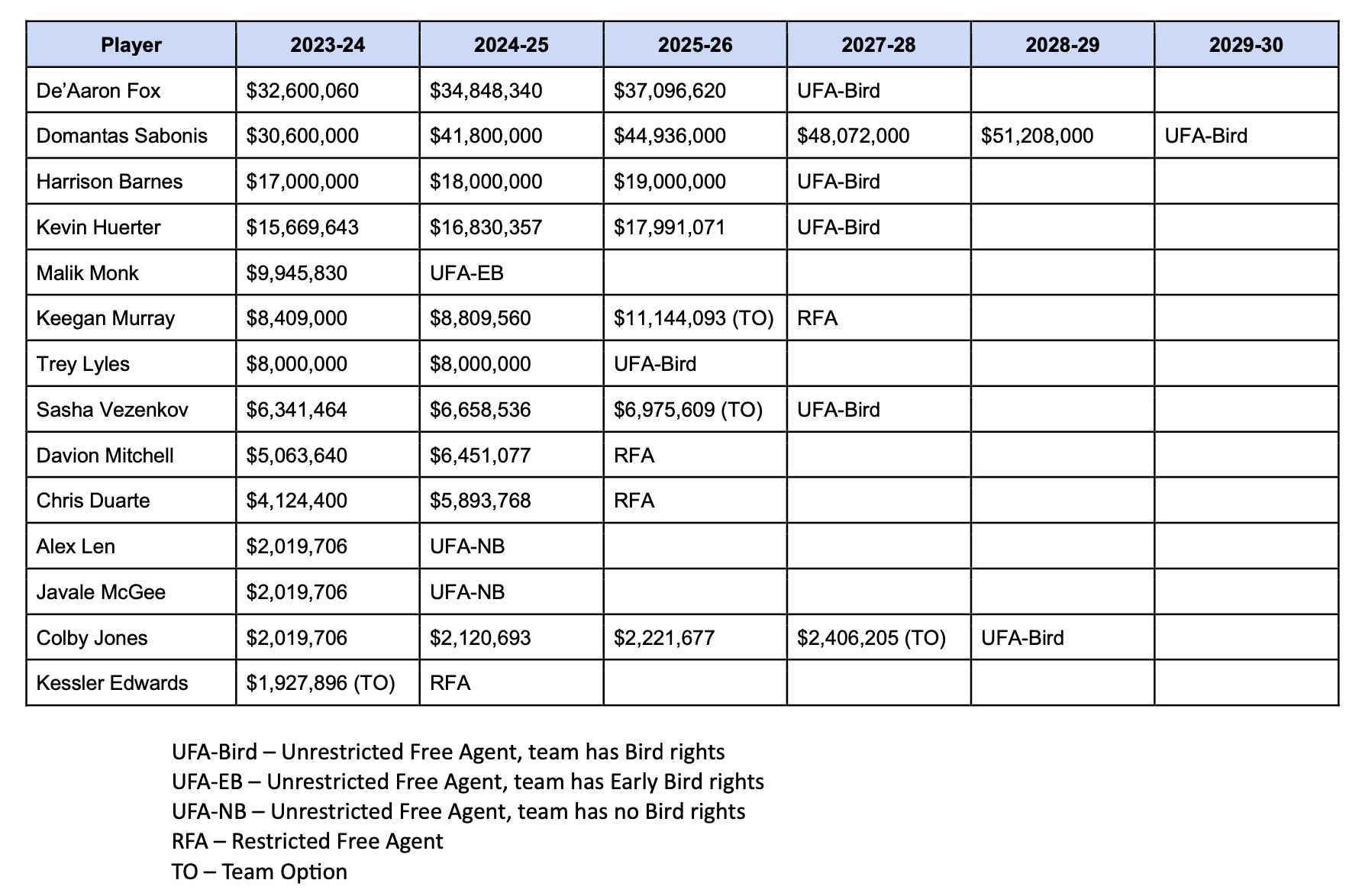

You can see a pretty comprehensive break-down of the Kings player contracts on Spotrac, but for convenience, the chart below shows the team’s player contracts (excluding 10-day contracts, two-way deals, and dead cap hits, which are pretty marginal and not worth charting for simplicity):

The Kings have two All-NBA caliber players under contract long-term in Fox and Sabonis, and there’s been no indication the team would even consider moving them. The team has also repeatedly shot down any notion of trading second-year player Keegan Murray, even in exchange for all-stars Pascal Siakam and Lauri Markkanen. That leaves the Kings with 12 roster players they can trade (plus one 10-day player, Juan Toscano-Anderson, and two-way players Keon Ellis, Jalen Slawson, and Jordan Ford).

Realistically, opposing teams are most likely to be interested in a handful of players—Murray (who the Kings refuse to trade), Harrison Barnes, Kevin Huerter, pending free agent Malik Monk, and Davion Mitchell—or future draft picks. The other players on the Kings roster could still be fit into a deal, either because someone wants to trade or to make salaries match, but their names don’t come up in trade rumors often because they’re not as appealing to other teams.

But we can’t just stop at listing the players the Kings might trade. We also have to look at a handful of key issues that influence who can be traded where as well as the value they have in a deal. The most important of these issues is salary matching, but I’ll also talk briefly about contract restrictions that could impact the trade value of players the Kings could consider dealing.

[The below sections on Salary Matching and Contract Restrictions are pretty granular. If you’re not interested, you can skip it, but I do want folks to understand two concepts: (1) the NBA’s CBA has detailed rules governing how trades can be constructed, which can significantly impact which players are included in trades, and (2) the CBA also has rules governing re-signing players and player extensions that can impact how much value they have in a deal.]

Salary Matching

Player-for-player trades in the NBA require "salary matching.” This can get complicated, but the basic idea is that if a team wants to trade a player, they can only receive back players with salaries inside of a certain band (or specified amount).

The amount of salary that a team can receive back in a trade depends on a few factors, the most important of which are the amount of the outgoing player’s salary and the team’s overall salary cap position. [HoopsRumors has a solid summary if you want to get into the details more, but I’ve tried to simplify things below. Relatively speaking.]

Let’s start with the team’s salary cap position to get familiar with some of the terms that will help with understanding the salary matching rules.

The NBA’s salary cap is specified each year by the league based on a pre-set formula outlined in the league’s collective bargaining agreement (CBA). For the 2023-24 season, the NBA set the salary cap at $136,021,000—teams can thus operate below the cap, at the cap, or above the cap, and different rules can apply to them as a consequence. That said, there generally aren’t many restrictions for teams simply being at or above the cap.

[In case you’re wondering, the NBA has a “soft” salary cap—meaning there are various ways to go over the cap. These exceptions cover trades, re-signing players that were already under contract with the team the previous season, signing draft picks, signing new players at the veteran’s minimum salary, and signing players using various other specified salary cap exceptions. As a result, most competitive teams end up operating above the cap in any given season.]

The NBA also has a luxury tax threshold, which is based on the cap and set at $165,294,000 for the 2023-24 season. Luxury tax teams have to pay an additional luxury tax for any salary paid at or above the luxury tax threshold. For example, if a team’s 2023-24 salary is $170,000,000, in addition to paying their salary out to the players, they have to pay an additional $4,706,000 in luxury taxes to the league, which in turn gets distributed to the other teams who aren’t luxury tax payers.

The amount of luxury tax is based on the amount by which a team exceeds the luxury tax threshold, and it gets increasingly onerous as a team spends more and more beyond the luxury tax threshold. I’ve included an explanation below, but note that all of the underlined amounts will increase in the 2025-26 seasons and beyond, per the CBA.

Between $0 and $4,999,999 above the luxury tax, teams pay $1.25 in luxury tax per dollar they go over the luxury tax threshold.

Between $5 million and $9,999,999 above the luxury tax, teams pay $1.75 in luxury tax per dollar they go over the luxury tax threshold.

Between $10 million and $14,999,999 above the luxury tax, teams pay $2.50 in luxury tax per dollar they go over the luxury tax threshold.

Between $15 million and $19,999,999 above the luxury tax, teams pay $3.25 in luxury tax per dollar they go over the luxury tax threshold.

[Teams that repeatedly have salaries above the luxury tax threshold (based on CBA-specified formulas) can also be charged additional amounts as “repeater” tax. It’s the same concept as outlined above, but the prices get even higher.]

The practical effect of the luxury tax is that as a team spends more and more above the luxury tax threshold, their roster becomes more and more expensive—and they effectively give more and more money to their competitors who stay below the luxury tax threshold.

This can have a huge effect on the trade market, because teams that can afford to spend (think big market teams like the Warriors or the Knicks) are more willing/able to pay a tax on salary, while other teams often prefer to stay below the luxury tax threshold so they can get money back.

The NBA also sets two salary cap thresholds above the luxury tax threshold called the “first apron” and the “second apron.” For 2023-24, the first apron is $172,346,000 and the second apron is $182,794,000.

Teams with salaries at or above these two thresholds are subject to a variety of restrictions this season, and will be subject to additional penalties in future years of the current CBA. We don’t need to go into the details other than to keep in mind a couple concepts:

Next year, teams are going to face increasingly stiff restrictions and/or penalties for having team salaries above the first apron and the second apron;

Specifically at issue here, teams above the first apron (and of course the second apron) have to comply with stricter trade rules; and

Teams generally don’t want to exceed the first apron or the second apron unless they need to, as they will face significantly reduced roster flexibility once the rules take effect next season.

Lastly, there is a minimum team salary threshold—often referred to as the salary floor. For the 2023-24 season, the salary floor is $122,418,000. The salary floor is an issue far less frequently than the salary cap and luxury tax threshold, and gets less attention than the first and second aprons, but the basic idea is pretty simple. Teams have to have team salaries above the salary floor, and if they don’t, they get penalized. Those penalties come in the form of having to pay up to the salary floor anyway (for example, players on the team will get paid more even though they signed contracts for less); the team will be subject to “cap holds” that prevent the team from taking advantage salary cap space below the salary floor; and the team will get 50% less money in distributions from teams paying luxury tax (this will go down to no money starting in 2025-26).

The details here aren’t so important for our purposes. What is important is to understand that there is no real benefit to teams going below the salary floor, and they can suffer penalties for doing so.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about the salary matching requirement.

The amount of salary a team can get back in a trade depends on the outgoing player salary this season and the team’s overall salary (specifically, whether the team is above the first apron). For teams below the first apron, the following salary matching rules apply:

For outgoing salaries up to $7.5 million, the team can receive back a player whose salary equals 200% of the outgoing player salary + $250k.

For outgoing salaries above $7.5 million up to $29 million, the team can receive back a player whose salary equals outgoing player salary + $7.5 million.

For outgoing salaries above $29 million, the team can receive back a player whose salary equals 125% of the outgoing player salary + $250k.

To help understand the concept, think about a few simplified examples.

A team wants to trade away a player whose salary is $5 million, which falls under Category #1 above. The player they receive back can only be paid a salary that is up to $10.25 million.

2 x $5 million + $0.25 million = $10.25 million

A team wants to trade for a player that makes $25.5 million. The player they trade away must be paid a salary of at least $18 million—this is Category #2 above.

$18 million + $7.5 million = $25.5 million

A team wants to trade away a player who makes $30 million. The most they can take back in salary is $37.75 million—see Category #3 above.

1.25 x $30 million + $0.25 million = $37.75 million

The rules are simpler, but more restrictive for teams at or above the first apron. For first apron teams, they can only take back a player whose salary is up to 110% of the outgoing salary no matter what the outgoing salary is. In practice, this means that teams at or above the first apron have less wiggle room in trades and have to match salaries more closely—they can’t take players who earn more than 10% of the players they’re sending out in a deal. This will go down to 100% starting next season.

Right now, teams generally can also aggregate salaries of multiple players in trades. Put simply, this means that teams can combine the salaries of more than one player for salary matching purposes in trades. For example, if a team wants to trade two players for three players, the salary matching rules described above still apply—the “outgoing salaries” would be the combined salaries of the two players the team is trading away, and the incoming salaries would be the combined salaries of the three players coming back in the trade.

Here’s a simplified example:

The Spurs want to trade Players A and B to the Wizards in exchange for Players X, Y, and Z. Player A has a $20 million salary and Player B has a $12 million salary.

Meanwhile, Player X has a $18 million salary, Player Y has a $8 million salary, and Player Z has a $7 million salary.

The trade is allowed, regardless of whether either team is a first apron team, because it meets all the salary matching requirements.

$20 million (Player A) + $12 million (Player B) = $32 million in outgoing salary

$18 million (Player X) + $8 million (Player Y) + $7 million (Player Z) = $33 million

General rule (non first apron teams): 1.25 x $32 million = $40 million, which is greater than the $33 million in incoming salary to the Spurs

First Apron Rule: 1.10 x $32 million = $35.2 million, which is also greater than the $33 million in incoming salary to the Spurs.

Both rules would also obviously be satisfied from the Wizards' perspective, as their $33 million of outgoing salary is greater than the returning $32 million in salary they are getting back.

Following the 2023-24 season, teams above the first apron and second apron will start to face more and more restrictions on the salary they can take back in trades and whether they can aggregate salaries for trades. Among other things, teams at or above the first apron won’t be able to take back more than the amount of salary they send out in a trade, and teams at or above the second apron won’t be able to aggregate salaries for trades (aggregation of salaries is described more below).

Teams can also send out a limited amount of cash per year in trades and/or include future draft picks in trades (which have no value for salary matching purposes).

There are a number of other minor salary matching rules that can apply in limited cases, but hopefully that covers the meat of it!

Contract Restrictions

There are a bunch of rules governing NBA contracts that are largely driven by how much time the player has served in the NBA, most of which don’t really impact trade considerations. For example, veteran players typically have fewer restrictions (although there can be exceptions and weird things like no-trade clauses exist sometimes, but they’re pretty rare).

Most of the Kings players have standard NBA deals, so there aren’t really special considerations for teams to look at when trading for them. But a few are worth flagging:

Malik Monk is scheduled to be a free agent this off-season, and either the Kings (or any team they trade Monk to) would have his “Early Bird rights.” I won’t go into detail on Bird rights, but the gist is that Bird rights let a team re-sign its own players and exceed the salary cap. “Early Bird rights” rights are a more limited version of Bird rights, but they limit how much the team can pay the player in the first year of a new contract. In Monk’s case, if he were traded, a team would be able to offer him a contract for the 2024-25 season and beyond with a starting salary at about $17.4 million and also go over the salary cap.

This could ultimately limit Monk’s trade value if teams think that Monk would be offered substantially more than $17.4 million as a free agent (which is certainly possible if not likely). This is because the team trading for Monk would be limited to offering him a below market starting salary if his contract would push the team’s salary above the cap, which in turn would make it less likely that Monk actually re-ups with them.

Separately, a number of Kings players have contracts with team options: Keegan Murray and Sasha Vezenkov in 2025-26, and Colby Jones in 2027-28. This gives teams the right to choose whether to keep the player under contract during the option year, which gives the team added control and flexibility with the player’s future contract. This is generally seen as positive for the team and bolsters trade value—especially on (comparatively) low salary deals that may prove to be below market for the player.

Keegan Murray, Davion Mitchell, Chris Duarte, and Kessler Edwards are also still on their rookie contracts, so they are slated to eventually hit "restricted free agency” rather than “unrestricted free agency” (like the rest of the Kings players) in different years. Without going into detail, unrestricted free agents can generally sign wherever they like, but the team gets the chance to match any deal a restricted free agent signs with another team—conceptually like a right of first refusal. This is generally favorable for the team, as it gives them more leverage in negotiations for players that out-perform their rookie deals in particular.

As first round picks, Murray, Mitchell, and Duarte can also be offered extensions of their contracts for up to five years (by the Kings or an acquiring team).

Draft Picks

Everyone knows that future draft picks, especially first round picks, are extremely valuable in trades. Often, teams trading away players ahead of the trade deadline are trying to turn their focus to the future, so getting back future draft picks for current players is a natural strategy.

The chart below shows the draft picks that the Kings own (in black) and the draft picks they’ve traded away (in red).

The Kings Future Picks

* Sacramento owes its 2024 first round pick to Atlanta, but it is protected for the top 14 picks. If the pick does not convey to Atlanta in 2024, it rolls over to 2025, where it is protected for the top 12 picks. If the pick does not convey to Atlanta in 2025, it rolls over to 2026, where it is protected for the top 10 picks. If the Kings pick is in the top 10 in 2026, then Atlanta loses the right to receive a first round pick and instead will receive the Kings’ second round picks in 2026 and 2027.

The CBA Restricts Trading Future Picks

As you can see from the chart above, the Kings have all of their first round picks through 2030, except for a protected pick in 2024 that they owe to the Hawks (part of the trade for Kevin Huerter almost two years ago). That’s a good war chest for trades, as they have a number of picks that they can send out in exchange for players now.

But there are a few key rules to keep in mind that restrict what the Kings can trade away.

First, per the CBA, teams can only trade draft picks up to seven years in the future, hence why the chart above only goes out to 2030. Next year, teams will be permitted to trade picks out to 2031.

Second, there’s something called the Stepien Rule, which requires that teams have a future first round pick in every other draft. In effect, this means that a team can’t trade its first round picks in successive years. Generally speaking, this is pretty simple to figure out: if a team has traded away its pick in 2024, it cannot trade its 2025 pick, the team would only be able to trade its pick in 2026 and beyond. [The Stepien Rule only applies to first round picks because the perception is that a team trading all of its first round picks could really hamstring it in the future. Second round picks aren’t seen as quite so important.]

The combination of the two rules above means that a hypothetical team today could trade, at most, four of its future first round picks: 2024, 2026, 2028, and 2030.

Third, teams can place protections on the picks they send out. Pick protections are often structured so that they pick doesn’t convey if it falls in a particular draft slot. For example, the Kings 2024 first round pick will go to the Atlanta Hawks so long as it does not fall in the top 14 picks. If the pick falls anywhere between 15 and 30, the Hawks get the pick for the 2024 draft, otherwise the Kings keep it.

Trading a future unprotected first round pick will usually net way more back in a trade than trading a top 20 protected first round pick, for example. The unprotected pick has more opportunity to convey and of course has the chance to be higher in the draft, so it carries way more value to the team trading for it. Teams often use these protections heavily as a way to change the value of their picks so that each side to a deal gets appropriate value. Pick protections can bridge the gap between a team trading for a player who is not quite worth a future first round pick, but is better than a second round pick, and the counterparty who isn’t interested in getting multiple second round picks.

Teams have a lot of flexibility to negotiate protections on picks, so long as the pick conveys within seven years at most, if at all (there are other rules, but they’re not really relevant to pick value). In other words, the protection has to be structured so that the pick either goes to the other team within seven years or the obligation to give the pick extinguishes, or alternatively turns into some other kind of trade value (like multiple second round picks that convey right away). As you can probably guess, how much protection gets placed on a particular pick has an ENORMOUS impact on that pick’s value in a trade.

All together, this can really make trading future first round picks complicated.

Let’s look at the Kings 2024 first round pick set to be traded to the Hawks. As I noted above, that pick is top 14 protected in 2024, but if it doesn’t convey to the Hawks in 2024, it gets converted to a top 12 protected pick in 2025. Same thing if it doesn’t convey in 2025, it converts to a top 10 protected pick in 2026. And, just to add some more complexity, if the pick hasn’t conveyed and Kings are picking in the top 10 in 2026, the Hawks would instead get two second round picks in 2026 and 2027. The three rules listed above conspire to really limit what the Kings can trade right now.

Because the Kings have agreed to trade their 2024 first rounder, they can’t trade their first rounder in 2025 because of the Stepien Rule. But, because the Kings placed protections on their 2024 pick, there is no guarantee that it will actually convey to the Hawks in 2024—instead, the Kings let that pick effectively roll over to 2025. Because of that, the Kings also can’t trade their first round pick in 2026, as it’s theoretically possible they would have already traded away their 2025 pick. The same situation would apply for their 2026 first round pick: because the Hawks could theoretically receive the Kings 2026 first round pick, the Kings can’t trade their 2027 first round pick under the Stepien Rule.

[1/16/24 addition: There is one caveat that I should add for completeness. The Kings can theoretically trade their 2026 first round pick if they structure the pick to be conditional on the Kings 2024 first round pick actually being conveyed to the Hawks. In such a situation, the team that trades for the Kings 2026 first round pick would only be able to get that pick if the Kings 2024 first round pick actually falls outside the top 14, and thus is conveyed to the Hawks. Otherwise, the team trading for the Kings 2026 first rounder would have to get something else (such as second round picks, a later year first round pick, etc.) or nothing.]

So What Draft Picks Can the Kings Actually Trade?

This is something that I see lots of people mix up when talking about what future the Kings have available to trade.

As of today, for their first round picks, the Kings can either trade (A) two first rounders in 2028 and 2030 or (B) one first rounder in 2029. They cannot trade their first round picks in 2025, 2026, or 2027, even though they most likely will end up owning those picks, as a result of the current deal they have with the Hawks. All of the second round picks the Kings have, however, can be traded (other than the 2030 pick they owe to Indiana).

But that’s not the end of the story!

The Kings can, in theory, remove the protections on the 2024 first round pick they owe to Atlanta to ensure that it actually conveys in 2024. Doing so would allow the Kings to open up additional first round picks for trade, such that they could make up to three first rounders available (in 2026, 2028, and 2030).

There are two things that must be accounted for, though, before the Kings remove protection from the 2024 first round pick owed to the Hawks.

The first is obvious: removing protections is the same thing as giving away value. If the Kings were to remove the protections on the pick they owe to Atlanta, it would be the same as giving additional value in the form of a better pick in 2024—so, whatever potential trade for a player this year would have to take that into account.

The second issue is that the Kings can’t unilaterally change their deal with Atlanta. Instead, the two sides have to reach another deal to change the protections. What if the Hawks think that the 2024 draft is terrible, but the 2025 draft is great? If they think that, the Hawks may not want to remove the protections on the Kings’ 2024 pick because they think it is unlikely to convey (basically meaning they think the Kings won’t make the playoffs) and they’d rather take a shot at getting a first round pick in 2025. It’s unlikely the Hawks are betting on that now, with the Kings sitting at 5th in the West, but the 2024 draft isn’t very highly rated so they may want to gamble. Regardless, the real point is that the Kings may have to give up something to take the protections off of the 2024 first rounder they owe to the Hawks so that they can be more flexible trading first round picks this year.

[1/16/24 addition: I should also flag that the Kings can trade the unprotected portions of the first round picks they’ve conveyed to the Hawks, although they won’t have as much value as a stand-alone first round pick. The Kings retain the rights over their 2024 first round pick if it lands in the top 14 (same for the top 12 picks in 2025 and top 10 picks in 2026)—essentially the inverse of what they’ve traded away from the Hawks—so they can trade those pieces. In other words, even without changing the protections on the first round picks owed to the Hawks, the Kings are allowed to trade their 2024 first round pick protected for picks 16-30, and they could add on roll-over years like they did with the Hawks deal. First round picks with these kinds of protections can be hard to value, but a Kings trade partner could essentially bet against the Kings making the playoffs in 2024 (with rollovers to 2025 and 2026, for example) by taking the lottery-protected portion of the first round pick the Kings have already traded away.

It’s also worth noting that NBA teams also can do pick swaps. This isn’t the same as trading a pick, but teams can essentially trade away the option to swap picks with another team. In such a situation, the Kings would give another team the right to choose, after the draft order is set and before the draft, between the more favorable of the Kings pick and their own. This has much less value than a pick itself, as the trade counter-party has to send back their own first round pick if they elect to swap, but these swap rights do have trade value.]

Cash

Teams can also include cash consideration in trades. Cash consideration is often used for smaller deals to make sense, as sometimes a team wants to get off of a player’s contract because they don’t play much and aren’t in the team’s future plans. Unsurprisingly, there are rules in the CBA governing how much cash can be included to avoid rich teams throwing money at less wealthy teams for their best players, but because these are usually just used for smaller deals, they don’t come up a lot. I’m talking about them here primarily to acknowledge that these rules exist and have a small part to play in deadline deals of all sizes.

For the 2023-24 seasons, teams are limited to paying cash considerations to a total of $7.05 million for the season. Theoretically, this can be split up among several trades or included in one trade. The practical effect of this limit is that cash considerations are usually only relevant for small deals involving a player or two with relatively small salaries (at least by NBA standards), otherwise it ends up not making much sense. For example, cash considerations were part of the Kings-Nets deal last year that brought in Kessler Edwards—the Nets sent Kessler Edwards and cash to the Kings so that they didn’t have to pay his salary and lower their luxury tax bill.

Part Three Coming Soon!

In the next (and probably? hopefully? last) part of this series, I’m going to look at some of the trade candidates that reporters and pundits are suggesting the Kings might pursue. I’m hoping to look at these potential trade targets from a few angles: What areas of need would they help address (PLEASE DEFENSE!)? Who would the Kings likely have to send out the door in order to get them? And, what do the Kings need to think about with respect to future draft picks and salary cap space before actually making a trade?